What did minoans trade with other islands by key

Excavations reveal that pottery and writings from Crete after resemble those of mainland Greece more so than those of pre Crete. Knossos then served as the administrative center of Mycenean Crete, until it was destroyed by fire in Despite this, Cretan civilization began to further decline, and many Minoan sites were abandoned.

Khondros is one of few new sites to be settled during this period. The last Minoan site to fall was the isolated mountain town of Karfi, which was able to resist assimilation into the Mycenean culture until the early Iron Age.

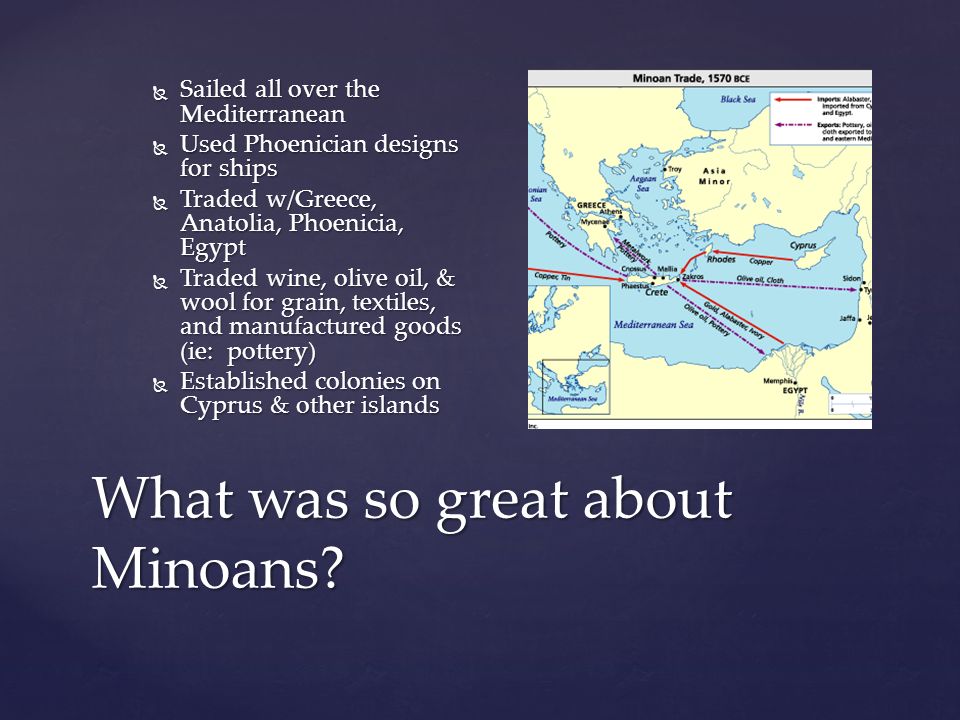

The widespread use of iron tools brought by the Myceneans rather than bronze ones used by Minoans is one of the main indications archaeologists used to determine the date of the final Minoan collapse. The Minoan culture featured a very distinctive religion, art style, and language. The Minoans were also pioneers in naval exploration, establishing several colonies on the Greek mainland and other Aegean islands, such as Akrotiri on Thera.

Minoan cultural influence spread throughout the region, including over the Mycenean culture. Many conclude there to be evidence of animal and human sacrifice in Minoan Crete during the palatial period. However, these sources are blurred and we should not come to any conclusions as yet, to whether sacrificial rituals did exist in Minoan Crete.

Although the Minoan religious system had come under much consideration and debate, it had never been fully explored, or written about in much depth. That is until when Sir Arthur Evans wrote his works on Minoan religion. Evans portrayed Crete as having an interconnection and a oneness. Evans is known as the advocator to this idea of unity and worship of a sole God. However, Minoan Crete was the perfect example for one to take and write about as it was secluded from other cultures as a lone island.

You could infer there to be evidence of them only worshiping one God, as there is a what looks like a Neolithic figurine of a goddess. This source is provided to us by the Spartan Museum. It portrays a woman holding two snakes suggeting her divineness, as it is believed to be a godess. The significance of the snakes around the arms is widely unknown however, they have survived for decades and in great numbers which shows the significance of it.

The importace to sarcaficial rituals is collosally important to link with them only worshiping one god. This is due to polothestic cultures utilising sacrifce for example rome to get good with the gods and get them in there favour. However, this is not evidance to lure us into any conclusion.

This is due to her coming across as if shes in an altrered state, holding in both hands snakes which highlights the unrealiablity of this theory. In the temple there were also many objects and another woman in the surrounding picture. However, in this image we see no evidance of any type of animal sacrafice. In the Toreador Fresco currently placed in the Palace of Knossos there is what looks like an image of three men and a bull.

However, it could also be a depiction of a sequence in changing a young boy into a man. This is due to the end figure being more pronounced than the others suggesting adult hood.

Another example of sacrifice is labeled a sacrifice by the Agia Triada sarcophagus. This pictorial image shows a slaughtered bull in the middle with two terrified animals under it.

We should take into account the double axe which is normally associated with bull sacrifice. Another interesting aspect is the appearance of a woman in this image as well. This has become a reoccurring theme throughout Minion Crete. We see her hovering her hands over the what appears to be an animal of the bovine variety which suggests prayer and worship. It also presents her as a priestess rather than a goddess which proves controversy towards the Neolithic figurine of a goddess we believed we previously saw.

Of late it is to be believed that Aarcheologists have found evidence of a sacrificial ritual, which included the sacrifice of animals, whose broken bones were found under a deposit of rubble. Though sacrificial rituals were an important part of the religious system there where many other important parts to it as well. Many outdoor shrines have been discovered some in caves, others on hill tops. There are depictions of women dancing around the trees, shaking the branches suggesting a sort of religious ceremony, further highlighting the role woman played.

Household shrines and shrines at tombs have also been discovered and this presents a real religious background to Minoan Crete.

Artifacts indicate that religious practice involved dance, procession, sacrifice and offerings, which where all key factors of the religious system. To further the theory of processions occurring or ceremonial events we gain and insight in the Saffron Gatherers fresco. This pictorial image shows two clear woman dancing around a monkey cannot be confirmed type figure. This further amplifies their role as they have appeared numerous times in sources.

Excavations have revealed frescoes, statues, and pottery. Pottery was the dominant art form of the Minoans from their arrival on Crete up until the Neopalatial period, when pottery-making technology allowed for a standardization of design. Fresco-painting soon rose in prominence, and focused heavily on religious and naturalistic themes.

Besides raw materials, the Minoans also adopted from the surrounding cultures artistic ideas and techniques as evident in Egypt's influence on the Minoan wall frescoes, and on goldsmithing production knowledge imported by Syria. The Minoans had developed significant naval power and for many centuries lived in contact with all the major civilizations of the time without being significantly threatened by external forces.

Their commercial contact with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia undeniably influenced their own culture, and the Minoan civilization in turn appeared as the forerunner of the Greek civilization. The Minoans are credited as the first European civilization. Archaeological evidence testifies to the island's habitation since the 7th millennium BC After the 5th millennium BC we find the first evidence of hand-made ceramic pottery which marks the beginning of the civilization Evans, the famed archaeologist who excavated Knossos, named "Minoan" after the legendary king Minos.

Evans divided the Minoan civilization into three eras on the basis of the stylistic changes of the pottery. Since this chronology posed several problems in studying the culture, professor N.

Platon has developed a chronology based on the palaces' destruction and reconstruction. We do not have much information about the very early Minoans before BC. We have seen the development of several minor settlements near the coast, and the beginning of burials in tholos tombs, as well as in caves around the island.

Neolithic life in ancient Crete consisted of major settlements at Myrtos and Mochlos. During this period the Minoans had contact with Egypt, Asia Minor, and Syria with whom they traded for copper, tin, ivory, and gold. The archaeological evidence reveals a decentralized culture with no powerful landlords and no centralized authority. The palaces of this period are focused around communities, and circular tholos tombs were the major architectural structures of the time.

The manner by which the dead were buried in these tombs indicate a society without hierarchical structure. The tholos tombs were used for centuries by entire villages, or clans and older corpses and offerings were placed aside to make room for a new burial. Older bones were removed from the tomb and placed in bone chambers outside the tholos structure. Most of the tholos tombs were circular while in Palekastro and Mochlos they were of a rectangular in shape with a flat roof.

The protopalatial era began with social upheaval, external dangers, and migrations from mainland Greece and Asia Minor. Around BC a new political system was established with authority concentrated around a central figure - a king. The first large palaces were founded and acted as centers for their respective communities, while at the same time they developed a bureaucratic administration which permeated Minoan society.

Distinctions between the classes forged a social hierarchy and divided the people into nobles, peasants, and perhaps slaves. After its tumultuous beginning, this was a peaceful and prosperous period for the Minoans who continued to trade with Egypt and the Middle East, while they constructed a paved road network to connect the major cultural centers. This period also marks the development of some settlements outside the palaces, and the end of the extensive use of tholos tombs.

The palaces of the period were destroyed in BC by forces unknown to us. Speculation blames the destruction either on a powerful earthquake, or on outside invaders. Despite the abrupt destruction of the palaces however, Minoan civilization continued to flourish.

The destroyed palaces were quickly rebuilt on the ruins to form even more spectacular structures. This is the time when Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Zakros were built, along side many smaller palaces which stretched along the Cretan landscape. Small towns developed near the palaces and the dead were buried in pithoi and larnakes, along rock-cut chambers and above-ground tholos tombs.

For the first time smaller residencies that we call villas appeared in the rural landscape, and were modeled after the large palaces with storage facilities, worship, and workshops. They appear to be lesser centers of power away from the palaces, and homes for affluent landlords. During this period we see evidence of administrative and economic unity throughout the island, and Minoan Crete reach its zenith.

Women played a powerful role in society, and the gold artifacts, seals, and spears speak of a very affluent upper class. The paved road network was vastly expanded to connect most major Minoan palaces and towns, and we have evidence of extensive trade activity. In the beginning of this era, Minoan culture dominates the Aegean islands and expands into the Peloponnese. We see its strong influence in the Argolis area during the Mycenaean time of grave circles, and in the southern Peloponnese, especially around Pylos.

The Minoan culture's fusion with the Helladic mainland Greek traditions of the time eventually morphed into the Mycenaean civilization, which in turn challenged the Minoan supremacy in the Aegean. For the first time, late in the Neopalatial period, the powerful fleet of the Minoans encountered competition from an emerging power from mainland Greece: Life on the island became more militaristic as evident by the large number of weapons which we find for the first time in royal tombs.

The affluence of the culture during this period is evident in the frescoes found in the Cretan palaces and in Thera, Melos, Kea, and Rodos. The end of this flourishing culture came with the destruction of most of the palaces and villas of the country side in the middle of the 15 century, and with the destruction of Knossos in During this late period there is evidence in tablets inscribed in Linear B language that the Mycenaeans controlled the entire island, while many Minoan sites were abandoned for a long time.

We cannot be certain of the causes for this sudden interruption of the Minoan civilization. However scholars have pointed to invasion of outside forces, or to the colossal eruption of the Thera volcano as likely causes. With the destruction of Knossos the power in the Aegean shifts to Mycenae. While both Knossos and Phaistos remain active centers of influence, they do not act as the central authority of the island any longer.

During the postpalatial period the western part of Crete flourishes. Several important settlements developed around Kasteli and Chania, while Minoan religion begins to exhibit influences from the Greek mainland.