PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA

5 stars based on

34 reviews

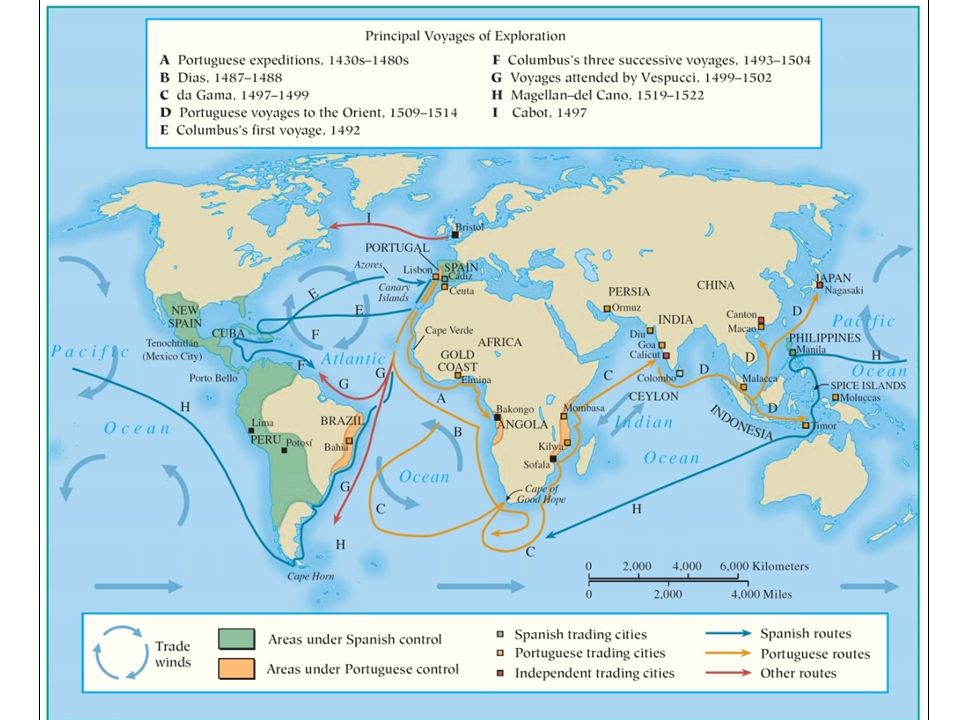

It was under the auspices of military-religious Orders, such as the Ordem Militar de Cristo Orders of Christand Ordem Militar de Santiago and Aviz successors to the Order of Knights Templar that Portugal was first granted legal and ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the new lands. This legal authority began with the conquest of Ceuta in Moroccan West Africa and extended to all discovered and conquered lands including the remote colony of Timor-Leste in The Lesser Sunda Portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock of Indonesia.

Under Papal authority, the prevailing international law of the time, Portugal was granted a monopoly over ecclesiastical and legal rights in the discovery or conquest of new lands. This international legal principle of Reconquista or Doctrine of Discovery as it is known today, was used to justify the domination of non-Christian, non-European peoples under the authority of the Christian God and is one of the earliest examples of accepted legal norms and principles that control the conduct of states over other portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock.

The Portuguese legal approach under Reconquista or Doctrine of Discovery can be summarized under four main principles: First, the Catholic Church had granted Portugal title and sovereignty over native peoples and their lands. Second, Portuguese exploration, conquest and colonization was designed to assist the Papacy in guardianship over all peoples of the world. Third, Portugal held monopoly rights over other European countries to colonize the world.

According to Portuguese historian Antonio Da Silva Rego from the Universidade Tecnica de Lisboa, it was taken for granted that Arabs or Muslims were excluded from any legal protection of international law and Papal Bulls. After-all Arabs and Muslims were the sworn enemies of Christianity and particularly the Portuguese.

Portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock Portuguese had waged war on the Moors from Old Portugal on national, religious, political and commercial grounds and were duty bound to continue to do so. But for non-Muslims, such as the native peoples of Africa, India, East Asia, and later Brazil another more benign legal tradition was applied.

The principles of legal governance adopted by the Portuguese Sovereign during this period were influenced by both ideological and pragmatic elements. Not only did Portugal have limited manpower to enforce lusitano laws but its primary focus was on individual enrichment and the spread of Christianity.

The former was linked to the rising development of humanism and increased secularization in Portugal in the early s. During this period many areas such as theology, science and law taught in Coimbra University drew largely from Castilian humanist influences of Salamanca University. Such influences shaped legal thought and natural law principles in Portugal at this time with particular relevance to discovery and conquest of new lands.

However should the Samuri oppose Portuguese trade, then the Portuguese position was quite different. Natural law stated that the freedom to trade and communicate between peoples is a natural means of human relationship and cannot portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock disrespected. If the Samuri of Calicut opposed trade then they were opposing the Portuguese rights as men of their natural human function. Such opposition ipso facto placed the Samuri outside the law and therefore would provide ample reason for the Portuguese to wage war on the Samuri.

At that time this was a uniquely progressive approach, which set aside the Portuguese from any other European colonising nation, creating a framework portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock a tolerant and liberal suzerainty, which the Portuguese propagated over its colonies and its peoples. Subsequent developments of international law relating to colonization drew upon the Portuguese approach and were expanded by influential theologian, priest and advisor to the Spanish Crown, Francisco de Victoria of the Universidade de Salamanca.

Such rights extended to the protection of their dominium or sovereign rights in accordance with natural law. However, De Vitoria also argued that under natural law native peoples were also bound not to violate the freedom of European colonizers to preach Christianity or trade and any such violations could be met with force. The discovery and conquest of Africa, and followed by India, South East Asia and later Brazil had come at a time when in 15th Century Portugal had suffered years of civil war and pestilence with its domestic economy in tatters.

Within Portuguese society there was growing social and economic demands to redeem their economic status and position, particularly amongst its disenfranchised young male aristocrats known as fidalguia or nobreza.

Customarily, with the backing of military orders or great noble families, fidalguia sought advancement in status and wealth through military and religious conquest, as well as mercantile rewards, via the manning of fleets seeking discovery and conquest of new lands. Spurred by an insatiable lusitano pursuit of trade portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock piracy, and fuelled by a zealous Christian mission to destroy all Arabs and Islamic enemies, the Portuguese fleets set out to establish numerous coastal trading posts in India, South East Asia, and later beyond to Brazil.

In this way, by the middle of the 16th Century, the Portuguese nobility had become inextricably linked to leasing parts of royal monopolies over trade routes in the form of viagens dos lugares or syndicated charters to merchants, fortress captains and aspiring underclasses.

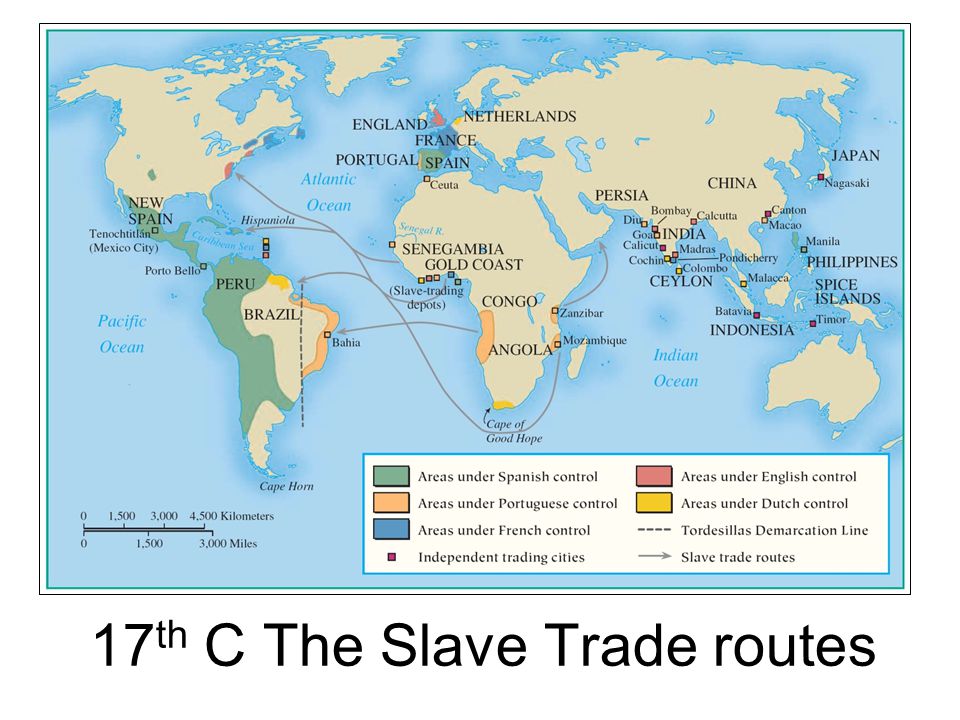

The ever expanding pyramid of monopoly leases, trade syndication and passage rights sold to merchants, soldiers and lower nobility classes became the dominant, if not sole economic engine of Portugal. In turn these foreign imports were funded by the ongoing expansion of Portuguese trading empire into Africa, Persia, India, China, Indonesia and beyond, bringing gold dust, ivory, slaves and spices.

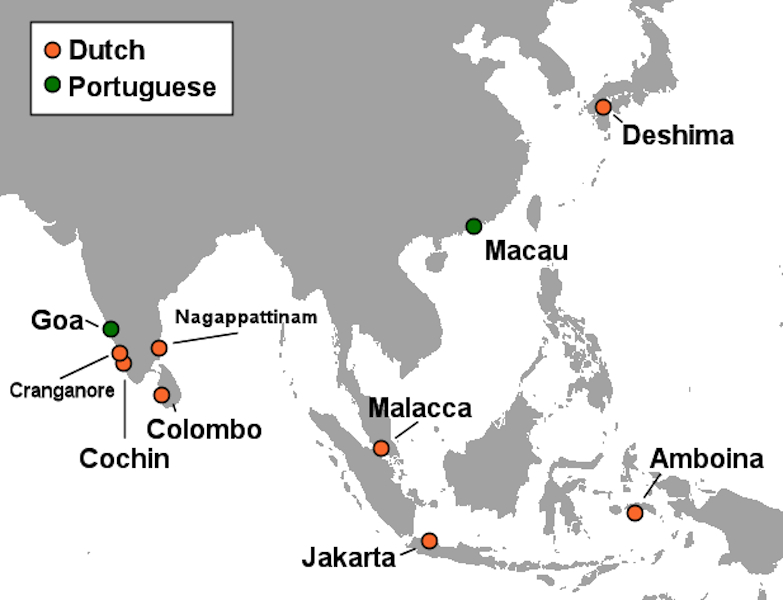

However, this expansion also saw the steady decline of domestic Portuguese agriculture and cloth production largely due to man-power and capital shortages. In addition, crown revenues also struggled to meet the ever growing demand for new ships and crews required by imperial expansion. Portuguese dominions in South East Asia, including Timor, operated loosely under the governance of the appointed governor and the council of Estado da India which from was headquartered in the city of Goa with the appointment of its first governor Dom Francisco de Almeida.

This vast and uniquely commercial network developed over maritime trade routes was typically governed a wide variety of political and legal arrangements, that the crown of Portugal carried out throughout the capitanias of South East Asia, often established in co-operation with its local rulers or by force.

Timor, as part of The Lesser Sunda Islands was the only capitania in the Estado da India outside the Indian sub-continent where the Portuguese extended authority beyond their feitorias trading-posts ,fortalezas forts and their local municipality, to cover a broader territory and larger populations, embracing both Christian and non-Christian alike. The Lesser Sunda Islands from an early date formed the hub of a Portuguese colonial administration in South East Asia safeguarding commercial interests, trade routes and Portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock missions, first in Solor, after in Larantuka on the island of Flores, and eventually Timor itself.

In typical Portuguese fashion colonial administration was often makeshift, under-manned and under resourced, whereby formal legal and local authority never really took hold outside the walls of their fortalezas.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese were faced with overwhelming hostility in The Lesser Sunda Islands region, particularly in Timor, where inter-tribal warfare amongst the liurais meaning tribal chieftain in Tetum challenged limited Portuguese military resources.

Even the missionary efforts of the Dominicans in Timor lagged behind their successes in Solor and Flores and did not improve until the mid-sixteenth century with the conversion of a number of chiefs of Timorese tribes to Christianity. These destabilizing factors prevented Portuguese settlement expansion inland beyond its small satellite coastal settlements of Solor, Larantuka and Timor.

Portuguese ships first sailed southward to the remote islands of The Lesser Sunda Islands including Timor, after the conquering Malaka on the west coast of Malaysia in pursuit of sandalwood. The captains of these ships had come to know of these islands from Chinese and Muslim traders. The most valuable and prized branco and amarelo varieties of sandalwood grew in abundance in Timor.

Branco and amarelo sandalwood were a sought after commodity in intra-Asian trade because the Chinese used it for joss sticks, perfume and fragrant coffins. Portuguese captains who bought sandalwood from Timor could sell it in Canton at three times the price, a fantastic margin considering the relatively short trade routes to Portuguese trading posts in Canton and Macao.

Timor also supplied beeswax, honey, ponies and native slaves in exchange for European cloth, tools and muskets. Portuguese maritime portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock indicate that Portuguese sailed to Timor regularly fromanchoring off it coast to trade with the ruling liurais.

So in order to protect and secure their lucrative sandalwood trade from Timor to Macao against local pirates, monsoonal storms as well as their Dutch rivals, portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock Portuguese set up small strategic satellite settlements on coastal vantage points. Such stepping-stone coastal settlements were within three to four sailing days of each other, along the portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock to Timor.

The first Portuguese feitoria was located in the southern Bay of Ende on the island of Flores, some two days sailing from Timor, consisting of a coastal settlement protected by an offshore island-fortress made of coral-rock and manned with Portuguese canons.

Then later, additional feitorias were established further eastward in Larantuka and on the Island of Solor located at the Eastern end of Flores Island. There is little doubt that the first Portuguese to portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock Timor were the S. Domingos Dominican friars from the nearby island of Solor.

The Dominican friars built a small stone fortress on Solor in known portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock Fortaleza de Henrique for the protection of native converts and around it grew the huts of Portuguese traders along with their native wives, children and servants. Only converts to Christianity were subject to Portuguese law and were granted Portuguese citizenship, a practice whereby race took second place to the over-coming Portuguese man-power shortages in remote South East Asian dominions.

In contrast to the Spanish, the Portuguese in the Estado da India did not attempt to replace indigenous laws by their own legal codes, instead the Portuguese preferred to graft onto their system, the customary law and legal systems they found in places where they settled.

Later, under assault from Dutch military in seeking to commandeer Solor and its sandalwood trade from the Portuguese, additional fortalezas were established and occupied in the islands of Flores and Timor by the Estado da India to safeguard its sandalwood monopoly.

Later, the Dutch conquest of Portuguese Malaka in saw a large outflow of Portuguese and their extensive following fled as refugees to Makassar in South Sulawesi. The port of Makassar was an important collecting centre for cloves, nutmeg and sandalwood from the Solor archipelago and Timor. The Topasses-Belum alliance formed a formidable local hegemony whose power and influence in Timor and Solor exceeded the official Portuguese military appointees, and also retained an unyielding hostility towards their Dutch usurpers.

Their influence was reluctantly recognised by the Portuguese Crown, motivated more from necessity than desire. More importantly, the Topasses as first co-inhabitants and defenders of the coastal settlements of Flores, Solor and Timor had developed a close mutual friendship and bond to the Dominican friars, mostly of Goanese descent.

For most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries both Topasses and the Dominican friars operated as the primary portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock of Portuguese authority and law in Timor and The Lesser Sunda Islands, often operating in defiance of official orders from Goa.

The Topasses, as traders in the Timor spoke both Malay and Tetum, however retained Portuguese as the language of sovereignty, law and faith as a badge of leadership and proud heritage. Boxer, provide a first-hand description of Topasses clans of Lifau: They speak Portuguese, and are of Romish religion, but they take the liberty to eat flesh when they please. They value themselves on the account of their religion and descent from the Portuguese; and would be very angry of a man should say they are not Portuguese.

A lthough these ruling clans of Laruntuka known as Larantuqueiros oscillated in their support of the Portuguese Crown, their control over coastal settlements of Laruntuka, Solor and Timor operated at most times without interference from the administration from Goa or Lisbon. The Estado da India was never really very interested in these remote island settlements, as they were occupied by a handful of white Portuguese traders, and largely administered by Dominican friars up and until official recognition by the Estado in Most historians agree that the ruling Topass clans or Larantuqueiros operated largely as an independent governing body and trade cartel over the annual sandalwood harvest, even though officially under the control of Estado da India.

In the clans of De Hornay and Da Costas and their troops established a coastal settlement in the fertile coastal lands of Lifau, in the present day former enclave of Oecusse on the Northern coast of Timor; and through a combination of force and barter with local liurais chieftains, gained control of the annual sandalwood harvest.

There is little doubt that the success of the Portuguese in maintaining a social, cultural and legal-political presence in Timor-Leste would not have been possible without the presence of the Topasses. Furthermore, it is clear that the Topasses in the Portuguese tradition maintained a strong and brutal authoritarian regime for over a century whereby arbitrary violence, rebellion and wars between rival clans and tribes was a feature of their rule. Dominican friars with help from local Topass traders began to build a fort at Kupang inlocated on a superb natural harbour on the far western coast of Timor.

Dutch traders sailed from Bativia with a large number of troops, over-running portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock fort and renaming it Fort Concordia. Open warfare between the sovereign Portuguese and Dutch forces ended with the Luso-Dutch Treaty ofbut it was not until that news of the treaty reached Timor.

The main impact of the Luso-Dutch Treaty was to divide Timor into two roughly equal regions: The treaty did little to quell the ongoing hostilities between the Dutch of Kupang, Topasses and warring tribes. However, the Luso-Dutch Treaty did spur Lisbon to made sporadic attempts to enforce their nominal authority over the ruling Topass clans, Timorese tribes and wayward Dominican friars.

Trapped by hostile forces and facing starvation, Guerreiro and his troops were forced to eat horses, dogs or whatever they could find, whereby Guerreiro finally capitulated and secretly fled Lifau on an English ship in Subsequent decades were dominated by inter-tribal warfare and battles between the Dutch traders of Kupang and the Portuguese settlers and Topasses of Lifau.

This ritual, literally a pax consange, consisting of a beverage of tua-sabo local brandy and sacrificed animal blood mixed with liurais and Topass blood. During this period, violent disputes between Dominican authorities in Malacca and local Portuguese governors in Lifau also helped to fuel insurrection. However, fortunately for the Portuguese, inter-tribal dissension and rivalries inevitably grew, allowing the Portuguese to gain the upper hand.

In commanded by white Portuguese officers, tribes loyal to the Portuguese numbering over four thousand attacked the rebel tribes in their head-quarters located in the crags of Mount Cailaco, and if not for the intervention of monsoonal rains the Portuguese forces would have annihilated the rebel tribes.

In a new Viceroy Colonel Pedro de Mello with fifty or so Maccanese troops arrived in Timor determined to finally destroy rebel tribes and allied Topasses. De Mello and his troops found themselves besieged and surrounded for over two months by hostile tribes at Manatuto on the muddy delta of Rebeiro Laclo, some seven or so kilometres east of the Portuguese fortress in Lifau.

Colonel de Mello and his troops, although half-starved and grossly outnumbered managed to launch a final heroic and bloody counter-attack killing a hundreds of rebel tribesman and taking hostage a number of liurais petty chieftains. However, ongoing power struggles between Dutch and Portuguese traders, successive Portuguese Portuguese control of the spice trade was ended by a rock and local Dominican friars, as well as ongoing tribal wars between Topass clans and liurais chieftains continued for nearly fifty years, with short periods of intermittent peace.

Nevertheless, the Topasses continued to fly the Portuguese flag over Lifau after de Menezes departure, and continued to control the seas between Timor and the eastern islands of Solor, Flores, Alor and Wetar.

From the second half of the eighteenth century, both legal authority and effective control over Timor by the Estado da India had stagnated and diminished along with its economic fortunes, faced with increasing incursions by the Dutch and other external factors. Historical accounts during this period by Dominican friars and Portuguese traders reveal numerous complaints to the Royal Court of Lisbon concerning the corrupt practices of Portuguese Viceroys in Goa and Macao.

These Portuguese officials not only participated in widespread bribe-taking but in the piracy of local shipping at the expense of Portuguese trade relations with other states. The beginning of the Napoleonic Wars in the early nineteenth century saw a further decline of Portuguese authority in Timor. The Portuguese Royal family had fled to Brazil to avoid capture by Napoleonic forces, and Timor as well as other settlements in South East Asia remained without direction from Lisbon.

The British warship H. Glatton had seized Kupang from the Dutch in abouthowever Western Timor was returned to the Dutch in which spurred a renewal of Luso-Dutch boundary disputes in the region.