Sha512 bitcoin news

41 comments

Blockchain wallet anonymous text messages

In a talk at CoinJar last fall, well-known bitcoin expert Andreas Antonopoulos made the following comment:. Will the requirements of recording every bitcoin transaction in the blockchain compromise its security because fewer users will keep a copy of the whole blockchain or its ability to handle a great number of transactions because new blocks on which transactions can be recorded are only produced at limited intervals? Bitcoin or, more generally, cryptocurrency mining serves several functions.

Mining allows the peer-to-peer network that bitcoin is composed of to agree on a canonical order of transactions, thus solving the double spend problem. Imagine a central arbiter or clearinghouse receiving transaction requests from clients to transfer money between parties. If the clearinghouse received two conflicting transactions i.

The key property that the clearinghouse has is omniscience — it has total knowledge of all account balances and pending transfers. Bitcoin partially does away with omniscience. In a peer-to-peer system, one does not generally have the expectation of knowledge of all messages. However, bitcoin transactions are intended to be broadcast one-to-all by peer forwarding. Thus, in principle, every network participant should have total knowledge of account states and pending transfers.

A problem arises when a malicious actor propagates two conflicting transactions to the network. The peer-to-peer network must decide which transaction came first and must invalidate the second. In broad terms, every transaction is confirmed by inclusion in a published block.

A block is simply a set of transactions plus some data, including a timestamp and the hash of the previous block. If anything in a block is later modified, one could compute its hash and will find a different value as the stated one with overwhelming probability , as such, one will not accept that block. Bitcoin solves the double spend problem by imposing that honest miners accept the first transaction that they see. That transaction is still unconfirmed until it is published in a block.

Blocks are found by mining, which is the process of expending computing power to solve cryptographic puzzles. Given a puzzle solution, a miner earns the right to publish a block and gain a reward for his service.

Interestingly, as Satoshi argued in the original whitepaper , this imbues bitcoin with subjective value. On receipt of a block, a miner may choose to accept it or not. If the block is valid i. A miner signals acceptance of a block by searching for subsequent blocks and including the hash of the received block into those blocks. Many bitcoin thinkers have argued that the returns to bitcoin mining with a large group of processors will cause a tendency toward a small number of miners or mining pools winning the majority of the blocks and, by consequence, having the most influence over the network.

This is a real security threat. Five is a small enough number that state-level actors could directly coerce all five entities without too much trouble. Five is also small enough that active collusion would be fairly easy to coordinate. Whether this distribution of mining power will be typical in the long run remains to be seen. The hope that the average hobbyist could fire up the client, donate a few clock-cycles and be welcomed into the bitcoin ecosystem with a block reward is now certainly dead.

The bitcoin blockchain is a massively replicated, append-only ledger. Its entries are transactions of various types, including transfers from one pseudonymous public key to another, coinbase transactions which mint new bitcoins , and transactions that encode and store some sort of metadata on the blockchain.

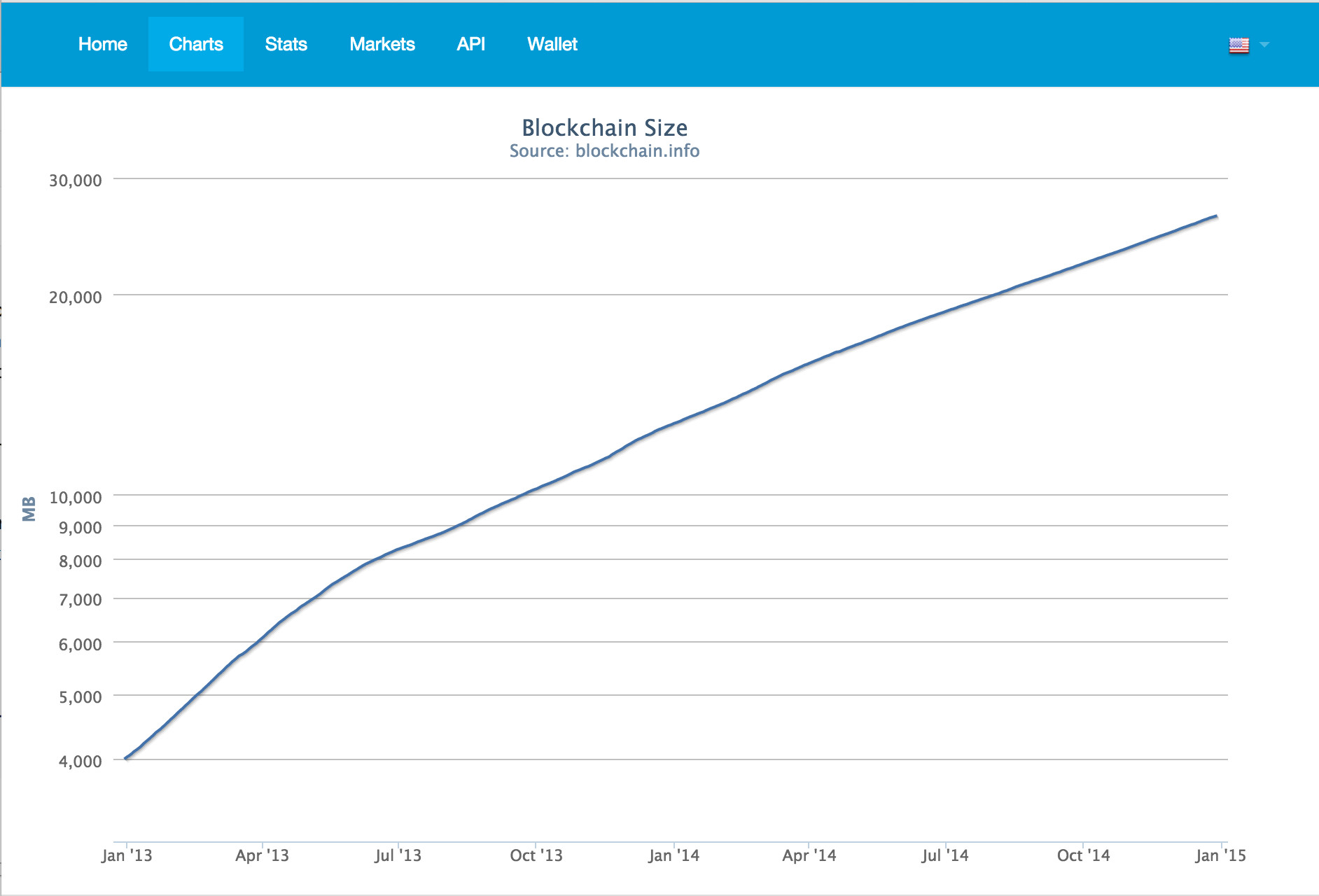

Full nodes must store the entire blockchain for the following reasons and more:. The bitcoin blockchain is presently about 25 GB in size. Downloading the blockchain peer-to-peer takes about 48 hours, and of course 25 GB of disk space. A log plot of the size of the blockchain over the last two years reveals an approximately linear trend:.

Computing a best fit line to the logarithmic data reveals an approximate factor of 1. To assess the extent to which disk space is a problem, we need to compare to projections for disk space.

Hard disk capacities per dollar have been flat for a few years , breaking a mostly exponential trend. As mentioned before, bitcoin balances are equivalent to the set of unspent transaction outputs on the blockchain. Each transaction creates one or more new unspent transaction outputs. To verify a new transfer from public key A to public key B, the bitcoin client does or did a search across the whole blockchain for transactions involving transaction outputs involving public key A, to verify that the unspent transaction output referenced in the transfer is truly unspent.

A possible optimization to this protocol is simply to store the set of currently unspent transaction outputs, rather than the whole blockchain history. Its growth probably tracks the size of the entire blockchain. One can use advanced data structures similar to Patricia trees to ensure that data encoding is efficient and that lookups are very fast.

Light clients allow the end user to interact with the bitcoin blockchain and to make and confirm transactions without committing the disk space and without the user experience overhead headache.

Light clients do not store the whole bitcoin blockchain, nor even the UTXO set. Rather, light clients allow users to receive lightweight proofs of the existence of certain UTXOs from miners, thus allowing the users to verify their balances. Light clients assume a certain amount of trust in miners to significantly reduce resource overhead. Suppose that a killer app emerges that massively increases the bitcoin transaction volume, far beyond the exponent predicted above.

What could we do then, to allow the average user to still run the full verification algorithm and be assured of his bitcoin holdings? One approach is a partial-sharding of the blockchain. Before we start rolling out the distributed hash tables, we assert that content-addressable solutions to blockchain storage are not immediately applicable.

The reason is that distributed responsibility schemes are not sybil proof — such schemes allow actors to be the judge in their own case s , so to speak, by pretending to be many distinct identities.

We could potentially shard the blockchain by replacing it with many independent blockchains, interoperating in a semi-trusted manner via cross-chain miners.

Cross-chain miners would facilitate transfers across different chains and respond to requests for lightweight proofs of the existence of transactions on distant chains. The end user could run a full mining and validating client on his main chain perhaps coded geographically or otherwise and could run light clients on other chains of interest.

Assuming that all these chains are mined, this brings up the immediate problem of security. The argument goes as follows — suppose there is a fixed universe of computational power to secure all the chains, and consider two scenarios:. A possible solution to this problem is merge-mining. Merge-mining refers to the possibility of mining blocks simultaneously across different chains. Namecoin , a sort of blockchain-based DNS protocol, is merge-mined.

One approach that has been suggested for scalability is for there to exist lightweight blockchains that are separate, but merge-mined with each other for security.

However, the problem is that in this setup, all miners would need to keep track of all blockchains or at least a majority of them for the merge-mining to be secure, and at this point there once again arises the need for a class of nodes to exist that process nearly every transaction, so we are right back at square one. Such schemes might involve some combination of multiple strategies. This means that an attacker would need to take over a substantial percentage of the entire blockchain in order to successfully corrupt even one shard, but at the same time only a very small number of validators need to actually process every transaction.

Solutions to this problem will differ depending on the specific approach. An average bitcoin transaction is about bytes. A cable modem, running optimally at 10 megabits per second can therefore facilitate 5, bitcoin transactions per second.

Bitcoin is nowhere near this bandwidth cap. Bitcoin blocks are hard-capped at 1 MB in size. Considering the amount of data that each transaction creates and the fact that the mining algorithm is set up to allow a new block every 10 minutes on average , this implies a theoretical limit of about seven transactions per second. When bitcoin transaction volume starts to push that limit, we might see fees go up or possibly changes to the bitcoin core.

This would require a hard fork, which is generally considered undesirable. Blockchain scalability is an essential set of issues that must be tackled as blockchain technologies become more popular.

He stayed at Princeton for another year, working as a scientific programmer in the Shaevitz Lab. He enrolled in the math department at UC-Berkeley in to study mathematical physics. He is one of the founding directors of the Cryptocurrency Research Group, a c 3 research body dedicated to the advancement of the understanding of Cryptocurrencies and related technologies.

Ninety odd years of banking source: The three main stumbling blocks to blockchain scalability are: The tendency toward centralization with a growing blockchain: The high processing fees currently paid for bitcoin transactions, and the potential for those fees to increase as the network grows.

The role of mining: Determining consensus and incentivizing participation Bitcoin or, more generally, cryptocurrency mining serves several functions. Trends toward centralization Many bitcoin thinkers have argued that the returns to bitcoin mining with a large group of processors will cause a tendency toward a small number of miners or mining pools winning the majority of the blocks and, by consequence, having the most influence over the network.

Click for a larger view. Growth Trend The bitcoin blockchain is a massively replicated, append-only ledger. Full nodes must store the entire blockchain for the following reasons and more: A log plot of the size of the blockchain over the last two years reveals an approximately linear trend: The UTXO set and prunability As mentioned before, bitcoin balances are equivalent to the set of unspent transaction outputs on the blockchain.

Light clients Light clients allow the end user to interact with the bitcoin blockchain and to make and confirm transactions without committing the disk space and without the user experience overhead headache.

Multiple chains, sharding and merge mining Suppose that a killer app emerges that massively increases the bitcoin transaction volume, far beyond the exponent predicted above.

The argument goes as follows — suppose there is a fixed universe of computational power to secure all the chains, and consider two scenarios: Bandwidth An average bitcoin transaction is about bytes.

Conclusion Blockchain scalability is an essential set of issues that must be tackled as blockchain technologies become more popular. Internet Archive Book Images.